Thank-you so much for being here.

Words cannot describe how grateful I am that you'd like to support my book! I won't make you wait until it's published. I'm sharing pieces of it here to give you a taste of what's coming. Please let me know what piques your interest!

Success Without the Self-Destruction: How to Quit The Burnout Club

Chapter 1 |

It's Not You (It's Work) |

Our conversation started with a sigh of resignation. Ginny, my new client, exhaled deeply and relaxed enough to say what she was really feeling. “I’m just waiting until my doctor tells me I need to go on leave for exhaustion, and the way work is going right now, that won’t be long.” If you’d glimpsed Ginny at your local coffee shop, you’d have no idea she was suffering; she was the picture of health and success. Ginny worked as a lawyer in a large firm where making partner was on her career agenda.

But the path to get there was proving punishing; long hours, high expectations, competitive co-workers, and high-demand clients were taking their toll. Plus, there was the “second shift” at home with 2 young kids and a spouse on disability – even her expertly applied makeup couldn’t completely hide the circles under her eyes. Ginny was being pulled apart. Quitting wasn’t an option, even though practicing law was no longer Ginny’s passion. Making partner would take the pressure off; it paid well, and she’d have more control over her hours and workload. What really excited Ginny about becoming partner was being able to support the up-and-coming lawyers in their firm. But first, she had to survive what was on her plate today, and right now, her long-game strategy was to burn out. Again.

The last time she burned out, it took her 6 weeks to get healthy, and every time she left on leave, she admitted it knocked back her chances of becoming partner. We were working together because her firm wanted to support Ginny’s career advancement. Ginny flatly stated she didn’t have time for coaching, yet our first conversation was a turning point. Hearing Ginny share her burnout experience, and the health and career implications, I was moved by how powerless she was. I asked her how it would feel to make partner without burning out? She burst into tears. Then, embarrassed by emotion she didn’t know was there, Ginny got angry at the whole circumstance she found herself in.

Despite the discouraging start to our work together, Ginny’s reaction gave me hope. Let me tell you why. She knows she’s burning out; her intuition and her body have been silently screaming this for a while, so that’s not news. What is news is Ginny’s newly awakened realization that it doesn’t have to be this way. She can make partner without self-destructing. Ginny is not alone; burnout has become a “badge of honor” many professional women feel is just a necessary part of being successful in demanding roles and organizations. So, despite what most of us already know about the state of our well-being (myself included), we aren’t listening to our intuition or our bodies. Do you ever wonder why?

I’m super curious about this because I believe every single one of us gets out of bed each and every day to do our best. If we can’t, we don’t go to work (because we’re bedridden). So, we go to work unwell expecting to do our best, despite what our intuition is telling us. The common belief is that if we can go to work and function, we’re not really that unwell to begin with. It’s become a common belief because no one taught us to measure the cost of going to work when our well-being is compromised, but our health isn’t. No one sets off in life to work themselves to death, trapped by their chosen career.

Of course, physical health is not the only way to measure well-being, something I learned the hard way after I continually pushed myself to go to work simply because I wasn’t feverish or throwing up. I ignored my intuition which knew very well my well-being was compromised. This led to a cycle of burning out, doing it not once but several times throughout my career (each episode taking more and more out of me). The last time I was lying in a hospital bed just waiting for the pain meds to kick in, I started to think that there has to be a better way to work, because I didn’t have any more of these cycles left to give. So, I paid more attention to what supported and what sabotaged well-being at work, not just for me, but for my friends, family and now for my clients. I discovered there are reasons why we don’t listen to our intuition despite knowing what the outcome will be.

These reasons have nothing to do with having a weak constitution, imposter syndrome, lack of experience or needing to be flawless to be recognized in a field of high-status colleagues. There are some very specific contributing factors that explain why you still go to work when you know it’s the last thing your well-being needs, and it’s time to call them out. Let’s start at the very beginning: in childhood. This deeply formative time of life has more influence on our risks for burnout and our ability to prevent it than many of us realize.

Work + Values

Your experiences as a child, from your parent’s approach to work to the socioeconomic story of your family, all sow the seeds for your work ethic and expectations about contributing to something meaningful (a purpose, your family, etc.). These experiences form the basis of your values and any biases about work (conscious and unconscious) that support or sabotage your well-being throughout your career and life, establishing your risk for burnout. So, how do we get from childhood to being at risk for burnout?

Work ethic. This phrase is an expletive in my world, and yet it’s an “ethic” we all have.

Growing up, we hear a lot of messages about work and having a work ethic. “Be responsible.” “Be accountable.” “You need a good work ethic.” “Hard work leads to success.” These messages are meant to support our success, but do they really achieve that end? Of course, they influence how you follow the example set by your parents and role models, sometimes without even knowing it (or against your better judgment). As with many caregiver influences, we respond in ways that are unique to us but predictable to humans; in the case of work ethic, there are four typical ways we do this:

You likely follow a mix of one of these four approaches. It’s never just one, yet it may not be something you’ve stopped to really think about. But this is the heart of your approach to work and your work ethic. Even if you consciously choose to follow in your caregivers’ footsteps, the world they worked in doesn’t exist anymore, making it difficult to replicate their results. It’s worth looking at what influences your approach to work. Consider whether you’re getting the results you desire because your experiences and choices (both conscious and unconscious) guide many of your working life decisions. They set the stage for both positive and negative impacts on your well-being, greatly influencing your burnout risk.

Work ethic as a concept seems simple enough. It’s been around for a long time, and everyone has their own interpretation of what “work ethic” means. Most of us learn what it means to our careers because it’s referenced as a good thing, but in practicality often means sacrificing something you hold dear to maintain status at work. It’s used as a way to guide people into choosing what’s right for their organization, but may not necessarily be what’s right for themselves. So, does the risk for burnout lie in our approach to work, or our work ethic? This can be a very “chicken or egg” question, one I have been grappling with for years, first as a human resource (HR) professional and now as a career coach. To ensure you and I are on the same page as we feel our way through this, we need a shared definition of work ethic. I define work ethic as:

There’s none of this humanity present (or even implied) in any definition of work ethic. Its focus is solely on productivity, which is why it’s a factor in burnout risk, and why we need to start questioning it as the “holy grail” of professional effort. Every one of us brings more to the table than what we get done in a day, our values and expertise offer much more to our organizations than just “productivity”. Be willing to see how society’s unexamined beliefs around work ethic are invisibly impacting expectations at the intersection of people’s careers and well-being, increasing your risk for burnout.

Of course, not all organizations force a choice between productivity and thriving at work, but some professions and organizations do in fact pit productivity against well-being, creating a twisted version of “Sophie’s Choice” for employees. When there’s an organizational focus on productivity, it can drive unhelpful management behaviors with respect to work/career expectations, expressed as “work ethic.” When organizations take a productivity-first approach to work without counterbalancing it with wellness responsibility, the collateral damage to humans is significant. Yet it’s invisible; the damage is inflicted under the surface, at an emotional level, impacting individuals’ confidence and trust in themselves. What I’ve witnessed demonstrates that until we re-examine our connection to the work ethic ethos and encourage different conversations and approaches with respect to our ways of working, we’re going to keep burning people out like they’re incandescent light bulbs.

Work + Money

We’re going to talk about money because it’s a significant burnout factor. We all need a reliable income to live our best life, so of course, it’s an important consideration in our careers; there’s a lot riding on a job that pays for your standard of living. Socioeconomics silently shape our behaviors and burnout risk, but unless you’re an economist, this isn’t something you’re likely thinking about. Yet, it has an enormous influence on your approach to work. My definition of socioeconomic influence is this:

Socioeconomic influences play an enormous part in defining our views about work, including how important (or not) emotional well-being is relative to the success and security of your job and the desired socioeconomic status it supports. Many of our work-based choices are referenced by the financial circumstances we experienced growing up, like not having enough money to buy the “cool” clothes and fit in with our peers, for example. Or watching parents/caregivers work long hours to ensure the next generation (yours) reaches a higher level of education and opportunity. Most parents want to give their children the same or better life than they had growing up, but this has become complicated. It’s more challenging to attain and maintain the same standard of living we had (or aspired to) growing up because of an ever-changing and demanding economic landscape. How far your money goes isn’t always in your control, but that doesn’t mean you won’t work hard trying to achieve/keep your desired standard of living.

Living well today is more than possible, but all of us have witnessed what can happen to someone’s standard of living when employment gets precarious and finances are stretched thin. It breaks financial security: It can also break up families. It can even break someone’s health. When we witness these experiences growing up within our own families and in the families of others, they form beliefs around the required trade-offs between work and well-being. We don’t think to question these beliefs that seem to have always been with us, like the air we breathe. The beliefs say, “Keep yourself employed, or you may lose your treasured lifestyle. Don’t risk everything you hold dear”. These thoughts contribute to the pressure and stress that create burnout risk.

Social and economic influences weigh heavy today, especially with messages such as, “Hard work is its own reward.” “Others will notice when your work is good.” “Don’t show weakness at work (or you may get fired).” “You have to go along to get along.”

These are mindsets modeled for us in childhood, teaching us how to be “successful” (as if there is only one way to get there, and it involves giving our power away). So, consciously or unconsciously, many of us carry these mindsets forward, influencing our ability to care for ourselves at work and in life. In contrast, what if these were statements you heard consistently growing up: “It’s healthy to take breaks during the day.” “Getting tired is a sign you need to rest, and that’s important.” “You know your limits better than anyone, so listen to them.”

A step towards figuring out how to have both your career and life support your emotional and physical well-being is recognizing your patterns based on what was present and what was absent in your childhood. How might these patterns be pitting your definition of success against your well-being? There’s room for both success and well-being in a thriving career, but it doesn’t just “happen.” Here’s why.

Work + Expectations

The impact work has on your well-being, the way work and life complement or compromise each other was probably never discussed in detail while you were growing up. Burnout likely never came up as a topic of dinner conversation. There is a natural conflict that arises between looking after your well-being while also being committed to having a career and a life that includes relationships. There are only so many hours in a day. The question becomes, why do these necessary things have to be at odds with each other? In a modern workplace, they often are, which has an impact on our mental health.

Mental health wasn’t always on the agenda in the past. As a kid, if someone your family knew had to step back from work for mental health reasons, there may have been compassion, but also some variation on the comment, “They’d better smarten up and get back to work!” expressing fear for this person’s employability. We cringe at this characterization of someone’s health needs today, yet stigma persists, and the fear is real. This is why many professionals have serious concerns about taking time off to meet their well-being needs or even reducing their working hours to a consistent 35-40 hours per week. Here’s why: You don’t have unconditional love at work. This relationship is very conditional. This is why many professionals think twice about proactively reducing their work commitments. They worry about taking the time they need to heal and get healthy when burnout (or other illness) occurs. The question looms: Could taking on less work, reducing my commitments, or stepping back from my job negatively influence my future career advancement or even my employability? Your intuition just answered that question, didn’t it? And I bet it screamed YES.

While society is generally more educated and compassionate about mental health, many employers still don’t take into account the need for emotional well-being at work. There is little concern for the systemic impacts on overall well-being that a workplace can present. All too often, there is unchecked demand for productivity either through naively optimistic strategic expectations or intentional practices that leave little room for discussion about individual needs. It doesn’t matter which. Either increase burnout risk in a workforce. If someone steps back for wellness reasons, questions are always raised that feed into the stereotype and stigma. This bias is not as apparent as it has been in the past, but still enough to make us all think twice before taking our doctor’s advice and proactively asking for what we need at work as a preventative measure against burnout and other illnesses. Sadly, you can get hurt over-committing to a desk job.

Sometimes, it’s our own beliefs and expectations that we “should” cope with what’s essentially harming us at work, whether it’s a toxic working environment, a terrible boss, or a high-demand workload. Regardless of what’s creating unrelenting stress at work, it’s all increasing our risk for burnout. There’s a phrase most of us use when it’s like this at work: It’s “fine,” as in: “It’s been really busy at work, but it’s fine.” The next time you catch yourself saying, “it’s fine,” ask your intuition if it’s really “fine.”

This is the “cost” of both an unexamined work ethic and socioeconomic concerns, which set the stage for how you approach work and the challenges it presents today. These expectations are carried forward not just from a career perspective but a family one as well. When my mom re-entered the workforce after my 2 siblings and I were in school, she worked full-time and still did the vast majority of the shopping, meal planning, cooking, laundry, and emotional labor (comforting us, chasing us to get our homework and chores done, etc.). It was the “norm” for the time, but the reality was she just added another 35 hours a week to the full-time job she already had at home. I never thought to question this approach until I had my own demanding career and young family and realized how bullshit carrying on with the same expectations really was. I decided I was NOT going to be the mom you could call at work to help you find lost things, but this was not an easy decision for me to take as I had to turn my back on the expectations and the modeled behavior I enjoyed growing up.

Expectations play a key role in determining your burnout risk. This goes for both the expectations of others and those you put on yourself. These expectations are rooted in childhood. It’s important to look at them without judgment. The experiences that set your expectations of yourself are what they are. There’s no one to blame here. It helps to recognize that everyone - your parents, grandparents, caregivers, etc. - did what they could to the best of their abilities. Whether your work ethic and response to socioeconomic influences is similar to your parents’ or is completely different, that approach was seeded in you during childhood. It’s something you’re using to accept and set the expectations you’re trying to meet, and using all this to make decisions that, consciously or unconsciously, influence your risk for burnout. But it may not be the only thing impacting your wellness because expectations, socioeconomic pressure, and work ethic can create the conditions for a form of trauma, and sadly, that’s not an exaggeration.

Work + Trauma

If you work in a high-pressure, precarious, or demanding role you have trauma. I see you frowning at that statement. I used to feel that way too before I learned what trauma really is. Trauma is a word we hear often. It’s a confusing concept because our society uses this word to describe so many things: heinous acts of personal defilement alongside descriptions of how a scene in a movie made you feel. “When the dog died, I was so traumatized!” Let’s examine it, because it’s playing a role in workplace wellness and burnout risk.

Trauma is a spectrum that covers many experiences, but here’s a way to identify with it that fits real life. Dr. Gabor Maté[i], MD, author and expert on trauma and healing, identifies two types of traumas which I’ll paraphrase:

Both types create stress that can be ever-present, reducing our capacity to bounce back from setbacks, access confidence, or feel like we belong. In his book The Myth of Normal, Dr. Maté explores our society’s collective perception of trauma, revealing that few among us experience big “T” trauma (thankfully). However, what gets minimized in our perception of trauma is the impact of frequent/persistent small “t” trauma. You may think if what’s hurting you isn’t incapacitating, if it isn’t as bad as what others have faced (big “T” trauma), it isn’t a big deal, right? That depends on the prevalence and frequency of small “t” trauma.

Here’s how I define trauma in its most basic form:

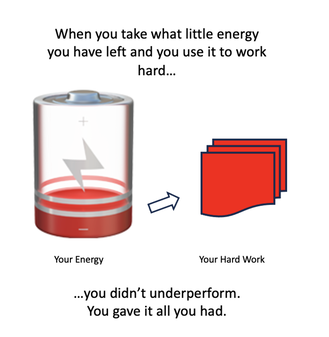

I truly believe that we are all good enough, even when we’re not at our best.

But the path to get there was proving punishing; long hours, high expectations, competitive co-workers, and high-demand clients were taking their toll. Plus, there was the “second shift” at home with 2 young kids and a spouse on disability – even her expertly applied makeup couldn’t completely hide the circles under her eyes. Ginny was being pulled apart. Quitting wasn’t an option, even though practicing law was no longer Ginny’s passion. Making partner would take the pressure off; it paid well, and she’d have more control over her hours and workload. What really excited Ginny about becoming partner was being able to support the up-and-coming lawyers in their firm. But first, she had to survive what was on her plate today, and right now, her long-game strategy was to burn out. Again.

The last time she burned out, it took her 6 weeks to get healthy, and every time she left on leave, she admitted it knocked back her chances of becoming partner. We were working together because her firm wanted to support Ginny’s career advancement. Ginny flatly stated she didn’t have time for coaching, yet our first conversation was a turning point. Hearing Ginny share her burnout experience, and the health and career implications, I was moved by how powerless she was. I asked her how it would feel to make partner without burning out? She burst into tears. Then, embarrassed by emotion she didn’t know was there, Ginny got angry at the whole circumstance she found herself in.

Despite the discouraging start to our work together, Ginny’s reaction gave me hope. Let me tell you why. She knows she’s burning out; her intuition and her body have been silently screaming this for a while, so that’s not news. What is news is Ginny’s newly awakened realization that it doesn’t have to be this way. She can make partner without self-destructing. Ginny is not alone; burnout has become a “badge of honor” many professional women feel is just a necessary part of being successful in demanding roles and organizations. So, despite what most of us already know about the state of our well-being (myself included), we aren’t listening to our intuition or our bodies. Do you ever wonder why?

I’m super curious about this because I believe every single one of us gets out of bed each and every day to do our best. If we can’t, we don’t go to work (because we’re bedridden). So, we go to work unwell expecting to do our best, despite what our intuition is telling us. The common belief is that if we can go to work and function, we’re not really that unwell to begin with. It’s become a common belief because no one taught us to measure the cost of going to work when our well-being is compromised, but our health isn’t. No one sets off in life to work themselves to death, trapped by their chosen career.

Of course, physical health is not the only way to measure well-being, something I learned the hard way after I continually pushed myself to go to work simply because I wasn’t feverish or throwing up. I ignored my intuition which knew very well my well-being was compromised. This led to a cycle of burning out, doing it not once but several times throughout my career (each episode taking more and more out of me). The last time I was lying in a hospital bed just waiting for the pain meds to kick in, I started to think that there has to be a better way to work, because I didn’t have any more of these cycles left to give. So, I paid more attention to what supported and what sabotaged well-being at work, not just for me, but for my friends, family and now for my clients. I discovered there are reasons why we don’t listen to our intuition despite knowing what the outcome will be.

These reasons have nothing to do with having a weak constitution, imposter syndrome, lack of experience or needing to be flawless to be recognized in a field of high-status colleagues. There are some very specific contributing factors that explain why you still go to work when you know it’s the last thing your well-being needs, and it’s time to call them out. Let’s start at the very beginning: in childhood. This deeply formative time of life has more influence on our risks for burnout and our ability to prevent it than many of us realize.

Work + Values

Your experiences as a child, from your parent’s approach to work to the socioeconomic story of your family, all sow the seeds for your work ethic and expectations about contributing to something meaningful (a purpose, your family, etc.). These experiences form the basis of your values and any biases about work (conscious and unconscious) that support or sabotage your well-being throughout your career and life, establishing your risk for burnout. So, how do we get from childhood to being at risk for burnout?

Work ethic. This phrase is an expletive in my world, and yet it’s an “ethic” we all have.

Growing up, we hear a lot of messages about work and having a work ethic. “Be responsible.” “Be accountable.” “You need a good work ethic.” “Hard work leads to success.” These messages are meant to support our success, but do they really achieve that end? Of course, they influence how you follow the example set by your parents and role models, sometimes without even knowing it (or against your better judgment). As with many caregiver influences, we respond in ways that are unique to us but predictable to humans; in the case of work ethic, there are four typical ways we do this:

- Some strive to imitate the approach to work and life their caregivers exemplified.

- Some choose to reject it.

- Some blindly follow in their caregivers’ work/life footsteps without questioning it.

- Some reject the path their caregivers created without realizing it.

You likely follow a mix of one of these four approaches. It’s never just one, yet it may not be something you’ve stopped to really think about. But this is the heart of your approach to work and your work ethic. Even if you consciously choose to follow in your caregivers’ footsteps, the world they worked in doesn’t exist anymore, making it difficult to replicate their results. It’s worth looking at what influences your approach to work. Consider whether you’re getting the results you desire because your experiences and choices (both conscious and unconscious) guide many of your working life decisions. They set the stage for both positive and negative impacts on your well-being, greatly influencing your burnout risk.

Work ethic as a concept seems simple enough. It’s been around for a long time, and everyone has their own interpretation of what “work ethic” means. Most of us learn what it means to our careers because it’s referenced as a good thing, but in practicality often means sacrificing something you hold dear to maintain status at work. It’s used as a way to guide people into choosing what’s right for their organization, but may not necessarily be what’s right for themselves. So, does the risk for burnout lie in our approach to work, or our work ethic? This can be a very “chicken or egg” question, one I have been grappling with for years, first as a human resource (HR) professional and now as a career coach. To ensure you and I are on the same page as we feel our way through this, we need a shared definition of work ethic. I define work ethic as:

- A set of beliefs defining the ideal approach to work for the benefit of a role model, leader or organizationwhich enhances your standing or security at work and/or within a group or community.

- A positive emotional connection to the work (meaning/purpose)

- Flexibility in where/how work is accomplished

- Genuine and meaningful recognition for effort and impact

- Consistent dignity, belonging, psychological safety and respect in the workplace, which includes sustainable work-loads and working hours

There’s none of this humanity present (or even implied) in any definition of work ethic. Its focus is solely on productivity, which is why it’s a factor in burnout risk, and why we need to start questioning it as the “holy grail” of professional effort. Every one of us brings more to the table than what we get done in a day, our values and expertise offer much more to our organizations than just “productivity”. Be willing to see how society’s unexamined beliefs around work ethic are invisibly impacting expectations at the intersection of people’s careers and well-being, increasing your risk for burnout.

Of course, not all organizations force a choice between productivity and thriving at work, but some professions and organizations do in fact pit productivity against well-being, creating a twisted version of “Sophie’s Choice” for employees. When there’s an organizational focus on productivity, it can drive unhelpful management behaviors with respect to work/career expectations, expressed as “work ethic.” When organizations take a productivity-first approach to work without counterbalancing it with wellness responsibility, the collateral damage to humans is significant. Yet it’s invisible; the damage is inflicted under the surface, at an emotional level, impacting individuals’ confidence and trust in themselves. What I’ve witnessed demonstrates that until we re-examine our connection to the work ethic ethos and encourage different conversations and approaches with respect to our ways of working, we’re going to keep burning people out like they’re incandescent light bulbs.

Work + Money

We’re going to talk about money because it’s a significant burnout factor. We all need a reliable income to live our best life, so of course, it’s an important consideration in our careers; there’s a lot riding on a job that pays for your standard of living. Socioeconomics silently shape our behaviors and burnout risk, but unless you’re an economist, this isn’t something you’re likely thinking about. Yet, it has an enormous influence on your approach to work. My definition of socioeconomic influence is this:

- The social and economic impacts that molded the world and society you live in today and affect how you want to live in this world, as well as your ability to achieve and sustain your desired lifestyle.

Socioeconomic influences play an enormous part in defining our views about work, including how important (or not) emotional well-being is relative to the success and security of your job and the desired socioeconomic status it supports. Many of our work-based choices are referenced by the financial circumstances we experienced growing up, like not having enough money to buy the “cool” clothes and fit in with our peers, for example. Or watching parents/caregivers work long hours to ensure the next generation (yours) reaches a higher level of education and opportunity. Most parents want to give their children the same or better life than they had growing up, but this has become complicated. It’s more challenging to attain and maintain the same standard of living we had (or aspired to) growing up because of an ever-changing and demanding economic landscape. How far your money goes isn’t always in your control, but that doesn’t mean you won’t work hard trying to achieve/keep your desired standard of living.

Living well today is more than possible, but all of us have witnessed what can happen to someone’s standard of living when employment gets precarious and finances are stretched thin. It breaks financial security: It can also break up families. It can even break someone’s health. When we witness these experiences growing up within our own families and in the families of others, they form beliefs around the required trade-offs between work and well-being. We don’t think to question these beliefs that seem to have always been with us, like the air we breathe. The beliefs say, “Keep yourself employed, or you may lose your treasured lifestyle. Don’t risk everything you hold dear”. These thoughts contribute to the pressure and stress that create burnout risk.

Social and economic influences weigh heavy today, especially with messages such as, “Hard work is its own reward.” “Others will notice when your work is good.” “Don’t show weakness at work (or you may get fired).” “You have to go along to get along.”

These are mindsets modeled for us in childhood, teaching us how to be “successful” (as if there is only one way to get there, and it involves giving our power away). So, consciously or unconsciously, many of us carry these mindsets forward, influencing our ability to care for ourselves at work and in life. In contrast, what if these were statements you heard consistently growing up: “It’s healthy to take breaks during the day.” “Getting tired is a sign you need to rest, and that’s important.” “You know your limits better than anyone, so listen to them.”

- Would that change the way you learned to care for and advocate for yourself as an adult?

A step towards figuring out how to have both your career and life support your emotional and physical well-being is recognizing your patterns based on what was present and what was absent in your childhood. How might these patterns be pitting your definition of success against your well-being? There’s room for both success and well-being in a thriving career, but it doesn’t just “happen.” Here’s why.

Work + Expectations

The impact work has on your well-being, the way work and life complement or compromise each other was probably never discussed in detail while you were growing up. Burnout likely never came up as a topic of dinner conversation. There is a natural conflict that arises between looking after your well-being while also being committed to having a career and a life that includes relationships. There are only so many hours in a day. The question becomes, why do these necessary things have to be at odds with each other? In a modern workplace, they often are, which has an impact on our mental health.

Mental health wasn’t always on the agenda in the past. As a kid, if someone your family knew had to step back from work for mental health reasons, there may have been compassion, but also some variation on the comment, “They’d better smarten up and get back to work!” expressing fear for this person’s employability. We cringe at this characterization of someone’s health needs today, yet stigma persists, and the fear is real. This is why many professionals have serious concerns about taking time off to meet their well-being needs or even reducing their working hours to a consistent 35-40 hours per week. Here’s why: You don’t have unconditional love at work. This relationship is very conditional. This is why many professionals think twice about proactively reducing their work commitments. They worry about taking the time they need to heal and get healthy when burnout (or other illness) occurs. The question looms: Could taking on less work, reducing my commitments, or stepping back from my job negatively influence my future career advancement or even my employability? Your intuition just answered that question, didn’t it? And I bet it screamed YES.

While society is generally more educated and compassionate about mental health, many employers still don’t take into account the need for emotional well-being at work. There is little concern for the systemic impacts on overall well-being that a workplace can present. All too often, there is unchecked demand for productivity either through naively optimistic strategic expectations or intentional practices that leave little room for discussion about individual needs. It doesn’t matter which. Either increase burnout risk in a workforce. If someone steps back for wellness reasons, questions are always raised that feed into the stereotype and stigma. This bias is not as apparent as it has been in the past, but still enough to make us all think twice before taking our doctor’s advice and proactively asking for what we need at work as a preventative measure against burnout and other illnesses. Sadly, you can get hurt over-committing to a desk job.

Sometimes, it’s our own beliefs and expectations that we “should” cope with what’s essentially harming us at work, whether it’s a toxic working environment, a terrible boss, or a high-demand workload. Regardless of what’s creating unrelenting stress at work, it’s all increasing our risk for burnout. There’s a phrase most of us use when it’s like this at work: It’s “fine,” as in: “It’s been really busy at work, but it’s fine.” The next time you catch yourself saying, “it’s fine,” ask your intuition if it’s really “fine.”

This is the “cost” of both an unexamined work ethic and socioeconomic concerns, which set the stage for how you approach work and the challenges it presents today. These expectations are carried forward not just from a career perspective but a family one as well. When my mom re-entered the workforce after my 2 siblings and I were in school, she worked full-time and still did the vast majority of the shopping, meal planning, cooking, laundry, and emotional labor (comforting us, chasing us to get our homework and chores done, etc.). It was the “norm” for the time, but the reality was she just added another 35 hours a week to the full-time job she already had at home. I never thought to question this approach until I had my own demanding career and young family and realized how bullshit carrying on with the same expectations really was. I decided I was NOT going to be the mom you could call at work to help you find lost things, but this was not an easy decision for me to take as I had to turn my back on the expectations and the modeled behavior I enjoyed growing up.

Expectations play a key role in determining your burnout risk. This goes for both the expectations of others and those you put on yourself. These expectations are rooted in childhood. It’s important to look at them without judgment. The experiences that set your expectations of yourself are what they are. There’s no one to blame here. It helps to recognize that everyone - your parents, grandparents, caregivers, etc. - did what they could to the best of their abilities. Whether your work ethic and response to socioeconomic influences is similar to your parents’ or is completely different, that approach was seeded in you during childhood. It’s something you’re using to accept and set the expectations you’re trying to meet, and using all this to make decisions that, consciously or unconsciously, influence your risk for burnout. But it may not be the only thing impacting your wellness because expectations, socioeconomic pressure, and work ethic can create the conditions for a form of trauma, and sadly, that’s not an exaggeration.

Work + Trauma

If you work in a high-pressure, precarious, or demanding role you have trauma. I see you frowning at that statement. I used to feel that way too before I learned what trauma really is. Trauma is a word we hear often. It’s a confusing concept because our society uses this word to describe so many things: heinous acts of personal defilement alongside descriptions of how a scene in a movie made you feel. “When the dog died, I was so traumatized!” Let’s examine it, because it’s playing a role in workplace wellness and burnout risk.

Trauma is a spectrum that covers many experiences, but here’s a way to identify with it that fits real life. Dr. Gabor Maté[i], MD, author and expert on trauma and healing, identifies two types of traumas which I’ll paraphrase:

- Big “T” trauma comes from physical/psychological abuse, war, loss, accident/injury, or violence.

- Small “t” trauma comes from the less memorable but still upsetting frequent hardships everyone experiences.

Both types create stress that can be ever-present, reducing our capacity to bounce back from setbacks, access confidence, or feel like we belong. In his book The Myth of Normal, Dr. Maté explores our society’s collective perception of trauma, revealing that few among us experience big “T” trauma (thankfully). However, what gets minimized in our perception of trauma is the impact of frequent/persistent small “t” trauma. You may think if what’s hurting you isn’t incapacitating, if it isn’t as bad as what others have faced (big “T” trauma), it isn’t a big deal, right? That depends on the prevalence and frequency of small “t” trauma.

Here’s how I define trauma in its most basic form:

- Trauma happens when we are not cared for, recognized, respected, and accepted as we are by others or ourselves.

I truly believe that we are all good enough, even when we’re not at our best.

But the workplace has other ways of looking at this. We are expected to come in and produce consistently (regardless of workplace resources or life circumstances). Yet, I still have a hard time accepting “good enough” from myself. How about you? This succinctly explains the impact of small “t” trauma many people experience repeatedly at work, trying to meet an entity’s business needs, absent of their own, and not being consistently seen, heard, accepted, or recognized for their contributions along the way. According to Dr. Maté, there are more people living with small “t” trauma than without it. Small “t” trauma isn’t becoming the norm, it is the norm. I think we all see and feel this intuitively, whether for ourselves, our family, or others.

Let’s address the “so what?” in this because we all know everyone has to deal with life, and it isn’t always fair. We can’t just go around expecting others to know or accept our trauma and treat us accordingly.

True. But what isn’t acknowledged are the multiple layers of small “t” trauma that were laid down before most of us even got to the workplace (i.e., bullying, discrimination, childhood emotional neglect, etc.). These layers of small “t” trauma (everyday instances of not being seen, heard, or accepted) don’t act on us the way big “T” trauma does (violence, loss, etc.). There are similarities between the two that Dr. Maté urges us not to ignore because “both represent a fracturing of the self and one’s relationship to the world.”[ii]

This fracture sets the stage for the loss of connection to ourselves. Not all at once, but cumulatively through erosion, little by little over time, small “t” trauma after small “t” trauma. When this happens, you withdraw, not from the workplace, but from yourself. This is the emotional equivalent of stress fractures that disrupt your relationship with yourself, seeding disease in your emotional well-being and increasing your risk of burnout. When that’s happening, there’s little emotional capacity left to consistently support yourself through a demanding job and busy home life AND feel the confidence in yourself that’s needed to thrive.

Work + Disconnection

Most of us find ways of coping with the pressures of career and life, but coping doesn’t address the emotional fracture. It doesn’t always guarantee healthy coping mechanisms, either. Coping during emotional fracture, as opposed to healing, means you distance yourself from the anger, shame, powerlessness, or fear you feel. These uncomfortable feelings arise when you’re not seen or accepted by the very people who rely on you and whom you need to rely on (but may neither like nor trust). This is how you wake up years into your chosen profession and wonder how the career you worked so hard to have (Hello, Work Ethic) and are completely reliant on is now the reason you’re putting your needs last, losing yourself, your confidence and your well-being in the process. And you know this is happening because of the growing dread you feel about work every Sunday.

If this is happening to you, remember you aren’t alone (The Burnout Club has millions of members, all of whom have a healthy dread of Monday). If you’re thinking, But I’m no victim! I rise above by gathering my power back and figuring out a useful plan to make work better because I’m “adulting,” hear me out. On the surface, it feels rational and responsible to make yourself accountable for getting things back on track for yourself. So, where could that go wrong?

It goes wrong with the disconnect from yourself. You're coping, but you’re not healing. When this happens, your capacity to act on your intuition is diminished. Now, this is the same intuition that’s been trying desperately to get your attention, even going so far as to plague you with Monday dread. But it’s also the intuition you’ve grown to distrust because you’re emotionally fractured and disconnected from yourself. So, you try harder with the tools you have, turning to those that served you best in the past. You think tools like hard work can get you to “safety” since they got you this far. But the tools that served you well in the past are not up to the task of overcoming such an all-encompassing and formidable circumstance as emotional disconnection. Being fractured and withdrawn from yourself in an environment that just keeps demanding more of you, all while hiding your growing disease from others, is an impossible situation.

When you’re disconnected from yourself, you have small “t” trauma. You’re not consistently cared for, recognized, respected, or accepted for who you are. Check-in: If you’re spending energy hiding your true feelings from anyone, you’re disconnected. So, you’re forced to solve complex problems - each with its own accompanying emotional components - while holding back the anger, hurt, fear, or shame that small “t” trauma creates. You can’t help but burn out when that's where you start.

When you’re disconnected from your emotions and intuition - the very things you need to solve a problem - you end up with even more dis-ease. The lack of self-compassion, the eroded boundaries, the false hope, and growing feelings of powerlessness create deteriorating conditions. That’s when burnout really takes root. The way out is using the very emotions you’re trying to avoid. To do this, you must gain access to emotional objectivity, confidence, and the compassion needed to empower your intuition and guide yourself to solutions. But no one is taught how to feel unwelcome things and have them “be helpful.” Instead, you avoid disruptive feelings because you don’t have the emotional energy to deal with them. No judgment. This happens to everyone.

This may not be happening to you every day. Things get better, your perseverance and skills pay off, something changes, the kids get more independent, and you land a new role or a new boss. But when you’re in the midst of emotional disconnect, the “go-to” move is to try harder and harder. That’s work ethic. You’ll suppress what you really feel so you can stay positive and hyper-focused on progressively getting to a place where things feel safer. And, of course, you want to do all this as quickly as possible, before you get hurt, afraid, and angry again, all the while clouded by uncooperative emotions. It’s exhausting and contributes to maladapted coping mechanisms, which I define as those things we do over and over again expecting different results. It is a true story based on real events; just ask Einstein.

Maladapted coping increases emotional disconnect and the dis-ease that follows, even when you’re doing everything you can to stay physically healthy. Leaning into physical self-care is not enough. While emotional health and physical health are connected, they’re still very different things. When you keep trying yet can’t alleviate the frustration and pressure, and all this goes on for too long, the resulting stress means you’re headed for burnout.

Work + Disease

When you’re coping with small “t” trauma and the emotional disease this creates, it affects you physically. Our bodies have the capacity to reflect our emotional experience – not just in body language, but in physical health. Take stress as an example; it releases the hormones adrenaline and cortisol into your system, which helps your heart beat faster, and your body initiates a flight, fight, or freeze sequence based on your interpretation of the threat. How many times a day does that happen? It may be short-term, like when you have to do a nerve-wracking presentation in front of the board, but what happens when life throws more systemic issues your way? What about when a demanding job, financial pressure, growing kiddos, aging parents, and difficult relationships combine on a daily basis, making stress ever-present?

We all have stress triggers, but their frequency and severity must be taken into account because there are different types of stress triggers that greet you throughout your day and then replay in your mind to torment you at night. Here are my definitions for the common types of stress triggers humans experience, creating that hormone-filled stress response:

Stress comes for us all. There’s no avoiding it, and when you have too much of it, your body deals with the biological fallout in ways that impact your physical health, especially when stress triggers are popping up everywhere (home, work, etc.). Chronic stress happens when it all “hits the fan” but is also present through frequent stress triggers of all types that are persistent and layered; let me show you what I mean. As an “Oh, shit!” stressor recedes, a “What fresh hell is this?” stressor emerges to accompany a pre-existing “Check, please!” stressor, keeping you on high alert, constantly flooding your system with stress hormones (and leaving you feeling like you just can’t catch a break). Cortisol and adrenaline are meant to come and go in your body within short periods to help you overcome a threat, but when there are persistent stress triggers layered one on top of the other, your body is continually under the effect of these hormones. It’s the physical equivalent of driving a car that can only go 150 kmph.; not good for the car, even worse for the driver and anyone in their path.

Chronic stress keeps your rapid response system engaged, and the on-going presence of stress hormones that were only meant to be in your system a short time (but are now perpetual) has a damaging impact on your body’s immune function. In other words, you get sick. Burnout risk can mean catching repeated colds, experiencing mystery rashes, persistent indigestion or out-of-the-blue joint pain. Long term, it may include setting off an autoimmune disease or another condition that requires tests or hospitalization to treat, eventually becoming manageable, but may mean you’re not going back to the health you enjoyed before. Simply put, your body cannot continually be on high-alert without collateral damage somewhere, and eventually our bodies simply say “nope” and stop functioning at peak performance. Of course, most of us can’t afford to be so sick we’re away from work for any length of time because it affects our lifestyle and socioeconomic status. It adds stress and pressure through increased precariousness to our finances and employability, kicking us when we’re already down. So, you go to work even when you’re not well, adding to your burnout risk.

While health care has conquered many barriers, a new family of diseases has leapt past modern medicine. These diseases are pervasive, touching the lives of almost everyone in western society, directly or indirectly, with very little end in sight. They are autoimmune diseases. You likely know someone or may be that someone who lives with lupus, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, celiac disease, Graves or rheumatoid arthritis (to name just a few of the 80 autoimmune diseases identified so far).

There’s an emerging link between autoimmune disease, over-work (that which causes injury/illness) and stress. The damage here to health, well-being, people and families cannot be underestimated, and if it turns out there is a direct link to over-work, think about what that means for our relationship to work and our employers. This link is the focus of on-going scientific study, which will offer valuable insights in the future about the ways work impacts well-being, particularly for women who are much more likely to be affected by an autoimmune disease than men. 80% of sufferers are women. Here's the kicker: Modern medicine doesn’t know what your immune system’s threshold is for stress. It doesn’t know the point your immune system can no longer handle the stress and becomes compromised.

Being a “card-carrying” member of The Burnout Club has consequences.

Every single one of us who works for a living gets out of bed each and every day to do our best, but best for whom? This is the question we need to stay in touch with to defeat burnout. Many of our childhood influences are designed to set us up for success (like work ethic) in what can be an unforgiving socioeconomic system. However, these influences unintentionally create the invisible conditions for unchecked expectations, emotional disconnection, and disease, leading to higher burnout risk.

We need to listen to our intuition and see through the veil of hidden influences and best intentions to the truth: Our organizations will take all the hours we can spare to work for their benefit, but they assume we’re doing this from a place of choice, health, and well-being. That isn’t always the case, is it? Like Ginny, you too may feel trapped by a job that no longer does anything for you except pay the bills.

It’s not you, it’s work. You don’t have to burn out to be successful. We’ve pit success against our well-being for too long. It’s time to get angry at a status quo that doesn’t support you to have both, because you deserve to have both: a fabulous career and an amazing life. To do that, you need to understand how burnout sneaks up on you.

Chapter 1 End Notes

[i] Maté, Gabor MD with Maté, Daniel. “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture”. United States of America: Knoff Canada, 2022.

[ii] Maté, Gabor MD with Maté, Daniel. “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture”. United States of America: Knoff Canada, 2022, 23.

Let’s address the “so what?” in this because we all know everyone has to deal with life, and it isn’t always fair. We can’t just go around expecting others to know or accept our trauma and treat us accordingly.

True. But what isn’t acknowledged are the multiple layers of small “t” trauma that were laid down before most of us even got to the workplace (i.e., bullying, discrimination, childhood emotional neglect, etc.). These layers of small “t” trauma (everyday instances of not being seen, heard, or accepted) don’t act on us the way big “T” trauma does (violence, loss, etc.). There are similarities between the two that Dr. Maté urges us not to ignore because “both represent a fracturing of the self and one’s relationship to the world.”[ii]

This fracture sets the stage for the loss of connection to ourselves. Not all at once, but cumulatively through erosion, little by little over time, small “t” trauma after small “t” trauma. When this happens, you withdraw, not from the workplace, but from yourself. This is the emotional equivalent of stress fractures that disrupt your relationship with yourself, seeding disease in your emotional well-being and increasing your risk of burnout. When that’s happening, there’s little emotional capacity left to consistently support yourself through a demanding job and busy home life AND feel the confidence in yourself that’s needed to thrive.

Work + Disconnection

Most of us find ways of coping with the pressures of career and life, but coping doesn’t address the emotional fracture. It doesn’t always guarantee healthy coping mechanisms, either. Coping during emotional fracture, as opposed to healing, means you distance yourself from the anger, shame, powerlessness, or fear you feel. These uncomfortable feelings arise when you’re not seen or accepted by the very people who rely on you and whom you need to rely on (but may neither like nor trust). This is how you wake up years into your chosen profession and wonder how the career you worked so hard to have (Hello, Work Ethic) and are completely reliant on is now the reason you’re putting your needs last, losing yourself, your confidence and your well-being in the process. And you know this is happening because of the growing dread you feel about work every Sunday.

If this is happening to you, remember you aren’t alone (The Burnout Club has millions of members, all of whom have a healthy dread of Monday). If you’re thinking, But I’m no victim! I rise above by gathering my power back and figuring out a useful plan to make work better because I’m “adulting,” hear me out. On the surface, it feels rational and responsible to make yourself accountable for getting things back on track for yourself. So, where could that go wrong?

It goes wrong with the disconnect from yourself. You're coping, but you’re not healing. When this happens, your capacity to act on your intuition is diminished. Now, this is the same intuition that’s been trying desperately to get your attention, even going so far as to plague you with Monday dread. But it’s also the intuition you’ve grown to distrust because you’re emotionally fractured and disconnected from yourself. So, you try harder with the tools you have, turning to those that served you best in the past. You think tools like hard work can get you to “safety” since they got you this far. But the tools that served you well in the past are not up to the task of overcoming such an all-encompassing and formidable circumstance as emotional disconnection. Being fractured and withdrawn from yourself in an environment that just keeps demanding more of you, all while hiding your growing disease from others, is an impossible situation.

When you’re disconnected from yourself, you have small “t” trauma. You’re not consistently cared for, recognized, respected, or accepted for who you are. Check-in: If you’re spending energy hiding your true feelings from anyone, you’re disconnected. So, you’re forced to solve complex problems - each with its own accompanying emotional components - while holding back the anger, hurt, fear, or shame that small “t” trauma creates. You can’t help but burn out when that's where you start.

When you’re disconnected from your emotions and intuition - the very things you need to solve a problem - you end up with even more dis-ease. The lack of self-compassion, the eroded boundaries, the false hope, and growing feelings of powerlessness create deteriorating conditions. That’s when burnout really takes root. The way out is using the very emotions you’re trying to avoid. To do this, you must gain access to emotional objectivity, confidence, and the compassion needed to empower your intuition and guide yourself to solutions. But no one is taught how to feel unwelcome things and have them “be helpful.” Instead, you avoid disruptive feelings because you don’t have the emotional energy to deal with them. No judgment. This happens to everyone.

This may not be happening to you every day. Things get better, your perseverance and skills pay off, something changes, the kids get more independent, and you land a new role or a new boss. But when you’re in the midst of emotional disconnect, the “go-to” move is to try harder and harder. That’s work ethic. You’ll suppress what you really feel so you can stay positive and hyper-focused on progressively getting to a place where things feel safer. And, of course, you want to do all this as quickly as possible, before you get hurt, afraid, and angry again, all the while clouded by uncooperative emotions. It’s exhausting and contributes to maladapted coping mechanisms, which I define as those things we do over and over again expecting different results. It is a true story based on real events; just ask Einstein.

Maladapted coping increases emotional disconnect and the dis-ease that follows, even when you’re doing everything you can to stay physically healthy. Leaning into physical self-care is not enough. While emotional health and physical health are connected, they’re still very different things. When you keep trying yet can’t alleviate the frustration and pressure, and all this goes on for too long, the resulting stress means you’re headed for burnout.

Work + Disease

When you’re coping with small “t” trauma and the emotional disease this creates, it affects you physically. Our bodies have the capacity to reflect our emotional experience – not just in body language, but in physical health. Take stress as an example; it releases the hormones adrenaline and cortisol into your system, which helps your heart beat faster, and your body initiates a flight, fight, or freeze sequence based on your interpretation of the threat. How many times a day does that happen? It may be short-term, like when you have to do a nerve-wracking presentation in front of the board, but what happens when life throws more systemic issues your way? What about when a demanding job, financial pressure, growing kiddos, aging parents, and difficult relationships combine on a daily basis, making stress ever-present?

We all have stress triggers, but their frequency and severity must be taken into account because there are different types of stress triggers that greet you throughout your day and then replay in your mind to torment you at night. Here are my definitions for the common types of stress triggers humans experience, creating that hormone-filled stress response:

- “Oh, shit!” Moments: unwelcome surprises like spilling coffee on yourself, the dog throwing up on the carpet, or someone saying, “We need to talk…”.

- “What fresh hell is this?” Experiences: the perpetual but small everyday things that make life just that much more difficult, like traffic jams, laptop/software glitches or constantly having your concentration broken by interruptions.

- “Check, please!” Periods: life events that create ongoing stress you have to face whether you want to or not. These issues need to be resolved, like job loss, financial insecurity, divorce, etc. They are excruciating periods to go through and take time. The upside is that they have a completion point.

- “It’s all hitting the fan” Circumstances: those unwelcome quality-of-life-impacting circumstances that have no real resolution (i.e., they’re chronic), like a life-altering health diagnosis, terminal illness, or caring for someone you love who’s affected by a chronic or terminal illness (like Alzheimer’s, end-stage cancer, etc.).

Stress comes for us all. There’s no avoiding it, and when you have too much of it, your body deals with the biological fallout in ways that impact your physical health, especially when stress triggers are popping up everywhere (home, work, etc.). Chronic stress happens when it all “hits the fan” but is also present through frequent stress triggers of all types that are persistent and layered; let me show you what I mean. As an “Oh, shit!” stressor recedes, a “What fresh hell is this?” stressor emerges to accompany a pre-existing “Check, please!” stressor, keeping you on high alert, constantly flooding your system with stress hormones (and leaving you feeling like you just can’t catch a break). Cortisol and adrenaline are meant to come and go in your body within short periods to help you overcome a threat, but when there are persistent stress triggers layered one on top of the other, your body is continually under the effect of these hormones. It’s the physical equivalent of driving a car that can only go 150 kmph.; not good for the car, even worse for the driver and anyone in their path.

Chronic stress keeps your rapid response system engaged, and the on-going presence of stress hormones that were only meant to be in your system a short time (but are now perpetual) has a damaging impact on your body’s immune function. In other words, you get sick. Burnout risk can mean catching repeated colds, experiencing mystery rashes, persistent indigestion or out-of-the-blue joint pain. Long term, it may include setting off an autoimmune disease or another condition that requires tests or hospitalization to treat, eventually becoming manageable, but may mean you’re not going back to the health you enjoyed before. Simply put, your body cannot continually be on high-alert without collateral damage somewhere, and eventually our bodies simply say “nope” and stop functioning at peak performance. Of course, most of us can’t afford to be so sick we’re away from work for any length of time because it affects our lifestyle and socioeconomic status. It adds stress and pressure through increased precariousness to our finances and employability, kicking us when we’re already down. So, you go to work even when you’re not well, adding to your burnout risk.

While health care has conquered many barriers, a new family of diseases has leapt past modern medicine. These diseases are pervasive, touching the lives of almost everyone in western society, directly or indirectly, with very little end in sight. They are autoimmune diseases. You likely know someone or may be that someone who lives with lupus, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, celiac disease, Graves or rheumatoid arthritis (to name just a few of the 80 autoimmune diseases identified so far).

There’s an emerging link between autoimmune disease, over-work (that which causes injury/illness) and stress. The damage here to health, well-being, people and families cannot be underestimated, and if it turns out there is a direct link to over-work, think about what that means for our relationship to work and our employers. This link is the focus of on-going scientific study, which will offer valuable insights in the future about the ways work impacts well-being, particularly for women who are much more likely to be affected by an autoimmune disease than men. 80% of sufferers are women. Here's the kicker: Modern medicine doesn’t know what your immune system’s threshold is for stress. It doesn’t know the point your immune system can no longer handle the stress and becomes compromised.

Being a “card-carrying” member of The Burnout Club has consequences.

Every single one of us who works for a living gets out of bed each and every day to do our best, but best for whom? This is the question we need to stay in touch with to defeat burnout. Many of our childhood influences are designed to set us up for success (like work ethic) in what can be an unforgiving socioeconomic system. However, these influences unintentionally create the invisible conditions for unchecked expectations, emotional disconnection, and disease, leading to higher burnout risk.

We need to listen to our intuition and see through the veil of hidden influences and best intentions to the truth: Our organizations will take all the hours we can spare to work for their benefit, but they assume we’re doing this from a place of choice, health, and well-being. That isn’t always the case, is it? Like Ginny, you too may feel trapped by a job that no longer does anything for you except pay the bills.

It’s not you, it’s work. You don’t have to burn out to be successful. We’ve pit success against our well-being for too long. It’s time to get angry at a status quo that doesn’t support you to have both, because you deserve to have both: a fabulous career and an amazing life. To do that, you need to understand how burnout sneaks up on you.

Chapter 1 End Notes

[i] Maté, Gabor MD with Maté, Daniel. “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture”. United States of America: Knoff Canada, 2022.

[ii] Maté, Gabor MD with Maté, Daniel. “The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture”. United States of America: Knoff Canada, 2022, 23.

|